When Polycarp began his research on childhood immunization uptake in Kaduna State, Nigeria, he knew the challenges would be layered and deeply rooted in the everyday realities of families. His project, "Understanding Socio-economic and Cultural Determinants of Childhood Immunization Uptake," explored why many children remain under-immunized despite national efforts and public health campaigns. What he uncovered was a complex web of barriers—economic, cultural, structural, and systemic—that collectively shape a caregiver’s decision to seek out vaccines.

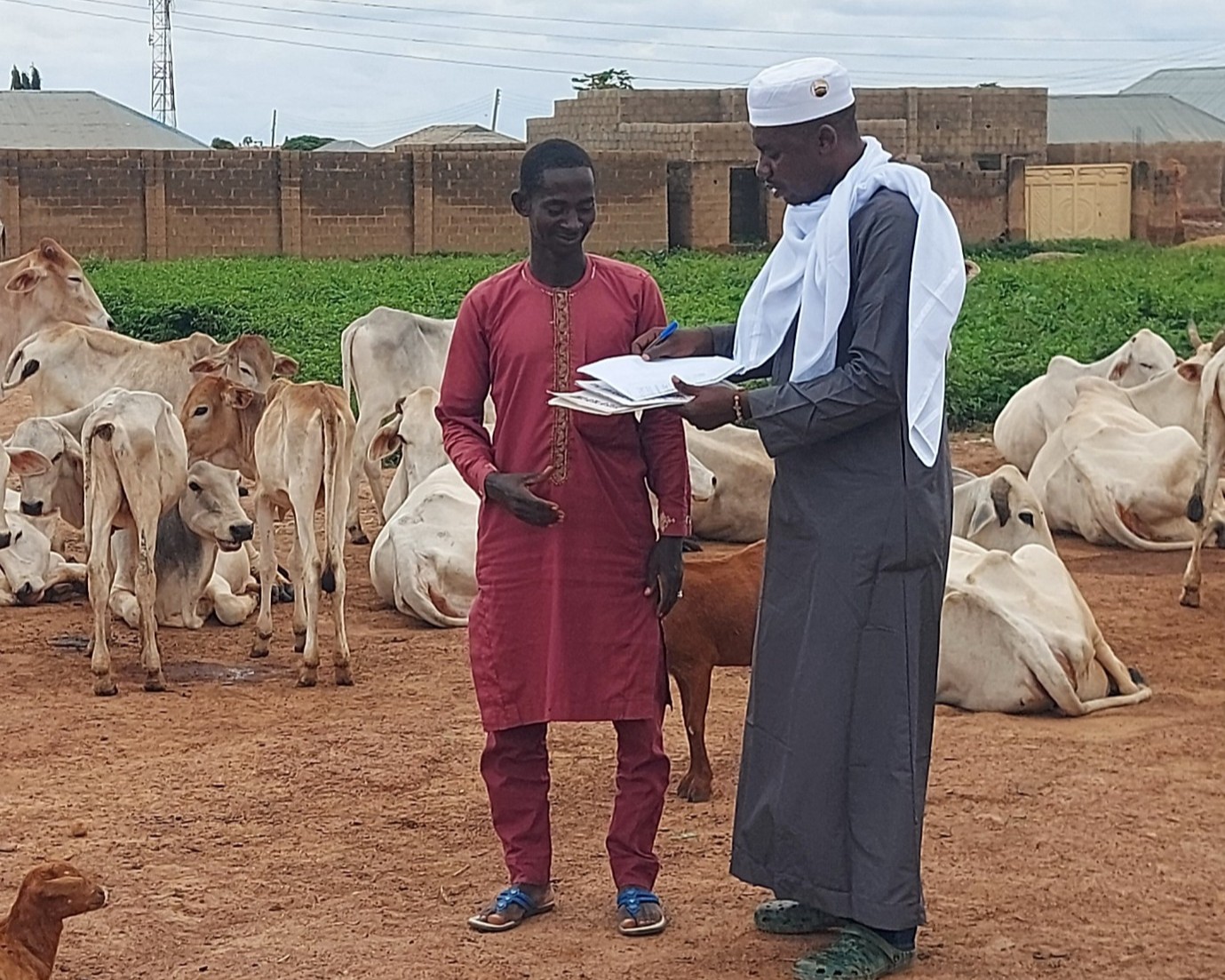

He began by visiting communities across the state, including hard-to-reach rural settlements and security-compromised urban areas. Before conducting interviews or focus groups, he prioritized community engagement, sitting with local leaders to explain the purpose of his research. These initial conversations, often held in traditional settings and conducted with great cultural sensitivity, were essential for gaining trust. Only with the approval of community elders could Polycarp and his team begin gathering stories and data.

A pattern of interwoven challenges emerged through focus group discussions with community members and leaders. Poor road infrastructure, long distances to clinics, and ongoing regional insecurity made access difficult, especially for families living in poverty or displacement. Insecurity was a recurring theme; many participants shared how safety concerns discouraged travel to health facilities, especially for women and young children. Others spoke of having to leave their homes entirely, causing lapses in care as they adjusted to life in new or temporary settings.

In-depth interviews with caregivers revealed how socio-economic stressors influence decision-making. One mother, for example, explained how the absence of family support, particularly from male partners, meant she had to choose between daily survival and walking hours to the nearest immunization center. Another spoke of how income instability made it impossible to afford transport, even when the vaccines were free.

In the quantitative phase of the study, Polycarp worked with immunization officers at local health facilities to examine vaccination records. The data revealed inconsistencies in vaccine uptake across communities and highlighted issues with record-keeping, supply chains, and staffing. Immunization staff confirmed what the field data suggested: the health system was under strain, and the burden of ensuring children were fully immunized often fell on families with the fewest resources.

What struck Polycarp most throughout this process was the willingness of people to share their experiences. Despite hardship and systemic failures, participants, especially mothers, spoke openly and with urgency. They wanted their stories heard. Many were deeply aware of the benefits of immunization but felt constrained by forces beyond their control: hunger, distance, social expectations, or the daily risks of insecurity.

The research process itself became a lesson in adaptive listening. While structured questionnaires offered a framework, Polycarp quickly learned the value of flexibility and allowing participants to guide the conversation and speak to what mattered most to them. In doing so, the study not only captured the data it set out to collect but also revealed new avenues for future inquiry and intervention.

Polycarp’s work in Kaduna underscores the importance of approaching public health challenges with both rigor and humility. Childhood immunization is not just a matter of access to vaccines; it is about transportation, trust, safety, gender roles, and the quiet resilience of communities navigating impossible trade-offs. His fieldwork calls for more than just improved services; it calls for solutions designed with and for the people who need them most.